2020 Democrats Can't Ignore Opportunities in Rural America

December 20, 2019#healthcare #election2020 #Democraticpresidentialcandidates #tariffs #hospitalclosures #farmers #ruralvoters

Two things can be true -- President Trump will win the rural vote next year, but if the election is decided by only thousands of votes in a few states, as it was in 2016, Democrats can win enough of them in rural areas to beat him.

For many 2016 Trump voters in rural counties, the president they love has made America great somewhere else. Schools and hospitals throughout their communities are closing; Trump's trade war, along with record flooding and drought, have devastated farmers whose bankruptcies now threaten the local economies they have long sustained; factories haven’t come back to these towns; the promised new infrastructure never came either; and no one got their health care repealed and replaced. President Trump and Republicans are most certainly not keeping doctors and jobs (or young people) in rural America.

Trump won rural voters by a 2-1 margin over Hillary Clinton and his approval rating among them remains higher than his national average. They are the linchpin to his Electoral College hopes. For many of these voters the choice is a binary one, and they will remain loyal to Trump for reasons beyond their pocketbooks, no matter what. But Democrats gained among this demographic in last year’s midterms in more than 50 congressional districts. From broadband and health care access, the expansion of Medicaid, support for increased production of ethanol and other biofuels to addressing a changing climate and disaster planning for farms, Democrats have a lot to discuss with the one in five Americans who live in rural counties.

Priorities USA, the Democratic Party super PAC, is spending big on digital ads, betting that even a small erosion in Trump’s support can make the difference in key states like Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania, which gave him the presidency by a margin of 77,744 votes combined. Groups such as Focus on Rural America are pitching progressive economic policies to these voters. American Bridge, another Democratic super PAC, has started a website documenting numerous Trump liabilities under such headlines as “Former GM Employee Blasts Trump for Broken Promises to Autoworkers.”

Wisconsin, election experts say, will decide who our next president is. It is also ground zero for the collapse of the dairy farm industry and where suicides have reached epidemic levels and farm loan delinquencies are at an 18-year high. Since January, more than 700 farms have closed -- an average of two per day -- and 44 schools have closed in dairy counties since 2018. Other farmers in the Upper Midwest have faced the same struggles. In addition to the loss of their markets in the trade war, record weather events prevented planting on 19 million acres of crops this year, the worst since the USDA began taking this measure in 2007.

Trump’s $28 billion relief package for farmers is more than twice the net amount of the 2008 auto bailout many Republicans vociferously opposed, but reporting by Bloomberg shows most of the money has gone to larger farms. The Environmental Working Group discovered through the Freedom of Information Act that while 80% of the recipients received average payments of approximately $5,136, the top 1% of them received 13% of the aid payments at an average of $177,000. At least three farms received $1 million and 45 farms were paid more than $500,000 because, though payments are capped at $250,000 per person, limits are ignored when partnerships allow family members in separate locations to receive payments. In addition to the damage from tariffs, farmers in Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa and South Dakota were irate over tariff waivers the administration granted to oil refiners that reduced production at, or threatened closure of, renewable fuel plants.

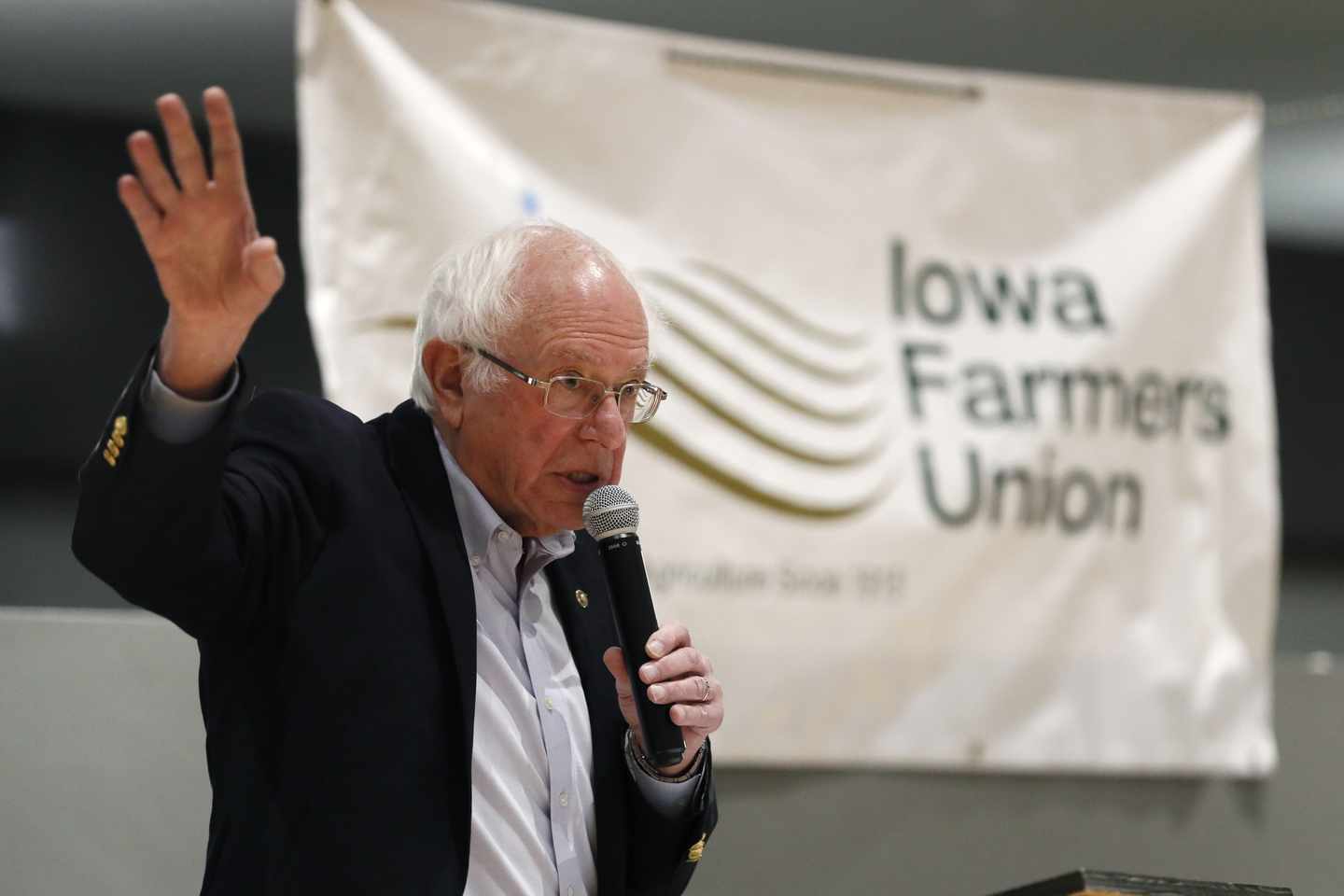

Trump continues to praise “patriot farmers,” trusting he will retain their support because many of them back his efforts to stand up to China. But his policies have earned rebukes from some in the agriculture sector. “Between burning bridges with all of our biggest trading partners and undermining our domestic biofuels industry, President Trump is making things worse, not better,” said Roger Johnson, president of the National Farmers Union.

As these Americans struggle to pay the bills, their health care is disappearing in a rural hospital closure crisis. Since 2010 more than 100 of these hospitals have shut down and 430 are in peril. Local mortality rates rise nearly 6% after each closure. Of the facilities at risk, 180 are in the 14 states that haven’t expanded Medicaid. While low patient volume at hospitals in emptying towns is to blame, so are low Medicaid reimbursement rates. Only 9% of primary care doctors practice in rural America, and those areas need more than 4,000 doctors to meet needs.

Republican opposition to Medicaid expansion, a factor in the disappearance of medical facilities in rural areas, is proving a potent political issue for Democrats in states with large rural populations. Last month Democrat Andy Beshear defeated GOP Gov. Matt Bevin in Kentucky and Democrat John Bel Edwards was reelected in Louisiana, largely on this issue. Democrats will campaign on it in swing states -- with rural voters -- that have not expanded Medicaid. Those include Texas, Wisconsin, Georgia, North Carolina, and Florida.

Most candidates in the Democratic primary race have rural agendas that focus mainly on health care, proposing the expansion of tele-health, assistance with transportation to far-away clinics and hospitals, as well as programs to reward and retain medical professionals in rural areas. Jason Grumet, president of the Bipartisan Policy Center, said most of the Democratic candidates' plans have been thoughtful and consistent but that Sen. Amy Klobuchar’s stands out as the most “authentically rural.” He noted that the anti-corporatist approach Sens. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren are taking with plans to break up Big Ag will resonate with voters experiencing firsthand the death of the family farm.

Former Sen. Joe Donnelly of Indiana said Democrats must show up in person to sell their plans in rural communities. He and fellow former Sen. Heidi Heitkamp of North Dakota, both defeated in red states in 2018, saw the party’s need to focus on this liability as soon as the midterm votes were counted. With their initiative, One Country, Heitkamp and Donnelly are talking to Democrats about outreach in communities the party has drifted from and, as a result, lost by dramatic margins. One of their main objectives is that candidates must not just have a rural program but need to campaign in places like Altoona and Clarion, Pa., Grand Rapids, Mich., and Fond du Lac, Wis., to talk to voters face to face. Donnelly said they are finding that campaigns and party officials are “appreciative and understanding,” and he is encouraged that most of them are spending much of their time on the ground in Iowa and New Hampshire with farmers and small business owners, whose support will be critical next November.

“So much of this comes down to a saying that has lasted a long time because it's true -- people don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care,” said Donnelly. “If they’re told every day on Fox News that you’re elitist and don’t believe in their values, people will believe that until you show up and tell them that’s not true. If we’re not there on a constant basis telling them we care about faith and family and strong borders, then it's going to be a tough election.”

Donnelly also noted that beyond access to health care and broadband, the eventual nominee will have to respect that the center of the electorate supports enforcement of immigration laws and a Hyde Amendment restricting the use of federal funds for abortion. And he had a warning to those in the party seeking to pull it too far to the left: “You win by adding people, not by kicking them off your team.”

Grumet said that beyond policy prescriptions, Democrats will have to work to earn voters’ trust. “The president has very successfully argued to rural voters that he is more like them, which is kind of a shocking accomplishment because he’s not a rural guy; he doesn’t even like Camp David,” he said, adding that the Democratic candidates must continue to confront the perception of elite, progressive condescension that undermined Clinton’s campaign in 2016.

Democrats should start by making the case that GOP policies did not prevent the hollowing out of rural communities and economies, nor has Trump been able to mitigate it. And if Democrats believe in the power of their ideas, they need to go and sell them everywhere. A Democratic nominee who doesn’t will end up like Clinton: on the losing end of a race with Trump.

Source: https://www.realclearpolitics.com/