Harris Ripped Biden on Race. As VP Contender, She Hails Him.

April 28, 2020#election2020 #JoeBiden #KamalaHarris

Sen. Kamala Harris tends to go to extremes when describing the choice for voters in the 2020 election.

During a virtual forum Monday to promote Joe Biden’s campaign -- an online gathering that also served as Harris’ latest veepstakes audition -- she implored his supporters to “do everything we can to elect” the former vice president because the November election is “literally going to be about our health and whether we live or die.”

In a normal election year, such apocalyptic language would prompt collective eye-rolls. But roughly two months into a pandemic that has upended the world, snuffing out precious lives and livelihoods in its path, it comes off as rehearsed gloom and doom from Democrats eager to use the crisis to oust Donald Trump from office.

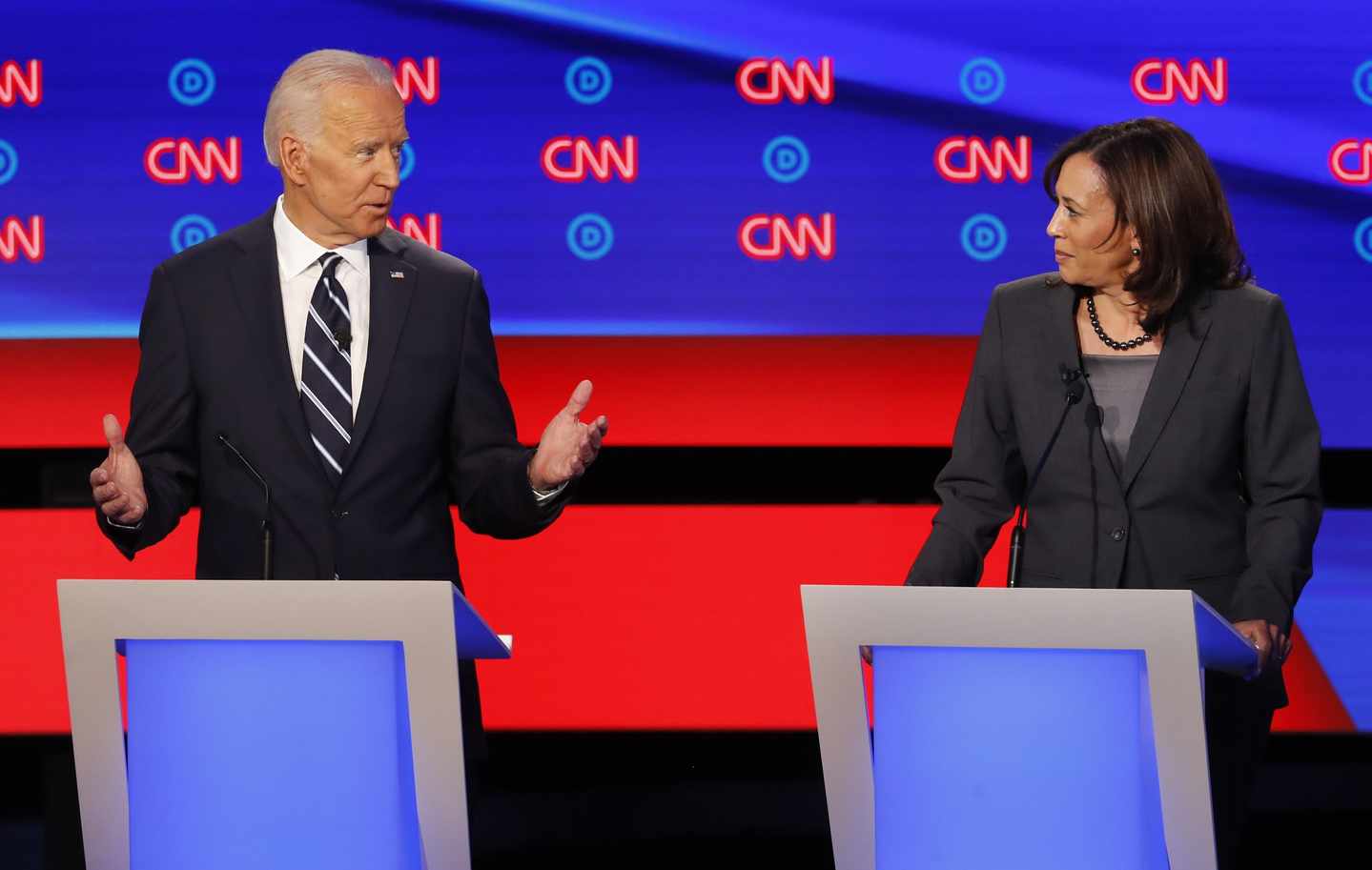

The problem, at least in terms of optics for Harris, is that less than a year ago the freshman California senator was making similarly unrestrained attacks against the candidate she now heralds as the nation’s savior. In fact, the only time her presidential campaign had even a short-term surge was when she upbraided Biden during the first primary debate over his decades-ago fight against busing to desegregate schools and his fond recollection of being able to work with segregationist senators in his first years in office.

As the only black woman on the stage, Harris said it was “hurtful” to hear him speak positively of those times in the 1970s. She described a little girl in California who was part of the second class to integrate her public schools and who was bused to school every day.

“And that little girl was me,” Harris said to dramatic effect.

Although she noted that she didn’t believe Biden is a racist, Harris used his comments as an example of why the Democratic Party still has a lot of reckoning to do when it comes to racial equality.

Fast-forward to Monday’s virtual forum on the “coronavirus’ disproportionate impact on communities of color” and it was as if last year’s confrontation had never occurred.

Harris heralded her former rival as the great equalizer when it comes to racial aspects of the pandemic — a champion of economic security, access to health care, food assistance and small business loans for black companies and churches — without a trace of the pain she had previously expressed about Biden’s past.

She praised him for producing a detailed plan for expanding the nation’s testing capabilities, including in areas where racial disparities could lead to undercounting, ensuring that recovery funds and small business loans are doled out equitably across the country, as well as expanding unemployment insurance and food assistance benefits.

“What Joe Biden is saying [is] there should be free testing and treatment for everyone, regardless of race. He is saying there should be an equitable allocation of recovery funds,” she said. “Joe always talks plain talk, he speaks straight — and what he’s saying is he wants to make sure every community gets enough so that it ends up being equal.”

Rep. Marcia Fudge, an Ohio Democrat and past chairwoman of the Congressional Black Caucus, quickly backed her up. “If we do not elect Joe Biden, we will not recover in my lifetime,” the 68-year-old lawmaker warned.

Political expediency during the general election is often the miracle cure for old primary wounds, perceived or real. In 2007, Biden’s cringeworthy comments about then-presidential candidate Barack Obama as “the first mainstream African American who is articulate and bright and clean and a nice-looking guy” evaporated into thin air when Obama tapped him as a running mate.

But those remarks, however awkward and inappropriate, were made in the classic bumbling, back-handed way that Democrats have come to expect during Biden’s long tenure on the political scene.

In contrast, Harris had engaged in a humiliating, full-frontal assault last year. Biden was clearly taken aback, telling the audience that her depiction mischaracterized his position. The moment went viral and led to a short-term boost in the polls for Harris.

Despite that short-term gain, the dramatic confrontation immediately triggered questions about whether she had sidelined herself from ever joining Biden on the Democratic ticket should the early front-runner secure the nomination. Harris aides have openly said they’re not sure the moment was worth it, especially when their boss wasn’t able to fully explain the differences she had with Biden on busing.

In an interview with CNN later that summer, Biden referred to Harris’ friendship with his late son, Beau, to explain why he was upset by the attack and didn’t see it coming.

“She knew Beau,” Biden said. “She knows me.”

Harris served as attorney general of California when Beau Biden held the same top legal post in Delaware, and the pair became friends while working on efforts to hold national banks responsible for the 2008 mortgage meltdown. Harris has since faced criticism for failing to speak out against then-Calif. Gov. Jerry Brown’s diversion of part of the state’s share of the $25 billion national settlement she helped negotiate, alongside Beau Biden.

The issue pitted homeowners who suffered foreclosures against the big banks, with Harris and other attorneys general as referees, and there is still lingering resentment from those who lost out on the relief.

“There were periods when I was taking heat, when Beau and I talked multiple times a day,” Harris wrote in her pre-campaign memoir, “The Truths We Hold.” “We had each other’s backs.”

The two were close and Harris expressed deep public condolences to the Biden family on May 30 last year, the anniversary of Beau’s death.

“Four years after his passing, I still miss him,” she wrote.

Perhaps it was the years of banked goodwill, or Biden’s decades of experience with Washington opportunism, that has allowed him to move beyond the debate attack. At the start of the second Democratic debate in Detroit last summer, Biden good-naturedly joked to Harris, “Go easy on me, kid.”

He has since said the two quickly recovered from the episode and have called each other often in the months since, sharing warm conversations and jokes. Both sides say they maintain a deep, mutual respect for the other.

“I’m not good at keeping hard feelings,” Biden said in December when asked if he harbored any ill will over the June debate clash.

After his Feb. 29 blowout victory in South Carolina, where the endorsement of elder statesmen Rep. Jim Clyburn helped him win 61% of black voters, both Harris and Sen. Cory Booker, who also campaign aggressively against Biden in the primary, quickly endorsed him. Booker, Harris, and Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer joined forces to campaign for Biden in Detroit in early March. After Harris opened the event, Biden bounded onstage and the two hugged, then held their hands in the air in solidarity.

The question now is whether Harris would be the right VP choice to bolster Biden’s pandemic-cloistered campaign, whether she has the credibility and personal charisma to help carry him over the finish line in November.

It’s clear she’s trying to make up for lost ground. After the hug in Detroit, Harris struck an emotional note. “I got to know Joe through Beau,” she told the crowd. “It’s a rare thing to see such a special relationship between a father and his son. It was an extraordinary relationship they had.”

During the virtual forum Monday, Harris extolled Biden’s personal tragedies as having molded him into the right man for this moment.

“He has a plan, he speaks from the heart, and understands people’s struggles, and he feels that struggle in a way that he always acts to take care of people and lift them up,” she concluded.

Source: https://www.realclearpolitics.com/