How Biden and Warren Can Mount a Comeback

February 17, 2020#election2020 #JoeBiden #ElizabethWarren #Democraticpresidentialcandidates

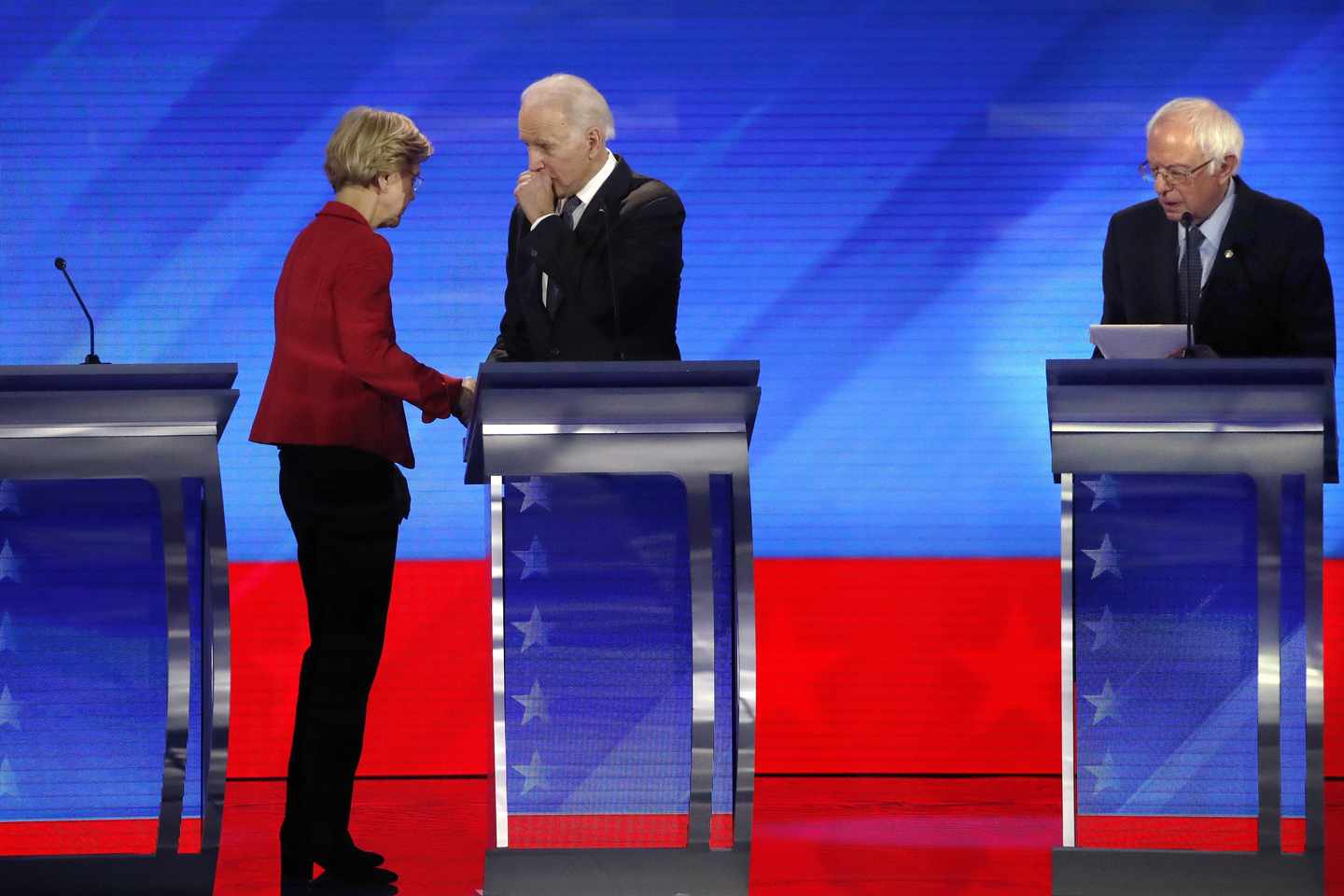

For much of 2019, the good money was on the Democrats’ presidential primary coming down to Joe Biden and Elizabeth Warren. Now both risk an early departure after humbling performances in Iowa and New Hampshire, with neither winning enough Granite State votes to earn a single delegate.

Winning the nomination after losing each of the first two contests is extremely rare. The only person to do it is Bill Clinton, and that’s in part because everyone ceded the 1992 Iowa caucuses to home state Sen. Tom Harkin, so it wasn’t interpreted as a real loss.

Super Tuesday is just two weeks away, and Biden and Warren will need to get up off the mat, snag a share of the 1,357 delegates available, or else their fundraising streams will dry up.

And yet, in this crazy field, you can’t completely count them out. Both have national followings and ample goodwill among the party faithful. The top three New Hampshire finishers—Bernie Sanders, Pete Buttigieg, Amy Klobuchar—all have narrow support and potential vulnerabilities that have not been fully scrutinized. The same goes for billionaire Michael Bloomberg, who has yet to appear on a primary ballot but is rising in the polls thanks to a saturation advertising campaign.

What is the path for Biden and Warren to get back in this race?

Biden has telegraphed his geographic path, which points south. That’s where Bill Clinton found his footing in 1992. He actually lost 10 of the first 11 states, but the first was a big win in Georgia. Then came a South Carolina landslide (plus a narrow Wyoming win), followed by a Super Tuesday blowout powered by six Southern or southerly Heartland wins, none of them close.

Biden too may find political Southern comfort. The 2020 Democratic primary is unusual in that it lacks a candidate with strong Southern ties—no Bill Clinton, no Al Gore, no John Edwards. Even Hillary Clinton, a New York transplant, had a long reign as first lady of Arkansas, helping her own the South in 2016.

In the current field, Biden has the strongest ties there. The U.S. Census deems Biden’s home state of Delaware as the Northeast edge of the South, plus he has regularly vacationed in South Carolina. If Biden wins South Carolina on Feb. 29, as the most recent poll suggests he can still do, that doesn’t just give him some delegates, but is also a good omen for the six Southern states on this year’s Super Tuesday.

Still, Biden risks having his campaign end in South Carolina, if voters stop believing he’s viable. After losing badly in two states, he can no longer rest his case strictly on electability vs. Donald Trump. Instead, Biden needs a sharper governability argument that draws blunt contrasts with his rivals.

He began to do this with Buttigieg after Iowa, releasing an online video harshly comparing their records. But in the following days, hesitant to come across as desperately negative, Biden flinched from pounding the ad’s message. He doesn’t have the luxury now of shying away from the jugular.

The former vice president should argue that because of Trump, the world is in utter disarray, and neither a former small city mayor nor a hedge fund billionaire like Tom Steyer (who has been rising in South Carolina polls with his own ad blitz) have anywhere close to the experience needed to deal with all of the global fires that need to be extinguished. And now that Klobuchar was unable to name the president of Mexico in a Telemundo interview, Biden can contrast her flub with the number of world leaders he knows personally (though Biden needs to be awfully careful he doesn’t make a similar mistake).

Warren is in an even tougher spot than Biden, for she has no obvious geographic path. The only state between now and Super Tuesday Warren is expected to win is her home state of Massachusetts, a deeply liberal state where a win won’t impress anyone and a loss would be the final nail in the campaign coffin.

Lacking a particular state to focus on, she should be focusing on her main obstacle: Bernie Sanders. They are competing for progressive populist voters, and he’s the one winning.

She has been loath to accept this political reality. The only person running she feels comfortable frontally attacking on a regular basis is Bloomberg, for trying to win the election through astronomic spending. Warren will attack others on similar grounds—she skewered Buttigieg for his high-dollar fundraiser in a “wine cave”—as it fits her persona as a crusader against Big Money and excessive wealth concentration. But unless she convinces more left-wing voters that she is the superior vehicle for their aspirations, Sanders will be the one carrying the left-wing banner into the Democratic National Convention.

Warren’s attempt to sideline Sanders has been to argue she can best unite the various strands of the Democratic Party, implicitly suggesting Sanders’ appeal is too narrow. That argument hasn’t flown because many on her left don’t care about uniting with the moderates, and those on her right see her as Sanders’ equal in polarization and unelectability. (Warren has also tried to emphasize her gender, but as Klobuchar has risen, that no longer distinguishes her from the men in the top tier.)

What can Warren do that she has not been doing? Leverage her reputation as the most rigorous policymaker in the field to paint Sanders as ill-prepared and ill-equipped to enact the progressive movement’s ambitious agenda.

Warren was burned badly when she, under pressure, released controversial details of her single-payer health care plan. Meanwhile, Sanders has skated while brazenly dismissing questions about the costs of his plans, single-payer and beyond. Warren should not let that stand, and she can use her past troubles to her advantage.

Steyer, who has been critical of single-payer as of late, has already put some money in a new Nevada ad savaging Sanders for trying to brush off the cost question on the “CBS Evening News.” Warren can amplify that attack, but with a twist: reminding folks that she had the courage to show her work on how to fund a single-payer system, that she took the hits for it, and that taking those hits was necessary for ultimate success. Why? Because “Medicare for All” can’t get passed if advocates can’t get outside the progressive bubble, explain to the public how the plan is actually going to work, and substantively respond to the inevitable criticisms.

Then she could twist the knife: If Sanders can’t explain it to the public, if all he can do is feed applause lines to his loyalists, then Congress and the Washington lobbyists are going to eat him alive.

Warren can then trade on her experience fighting tooth and nail to establish the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, to prove she knows how important it is to get the details right.

If that blow lands, Warren still may not be rewarded with a win in any state. But she might eat into Sanders’ numbers enough nationally to hold him back from winning more states with narrow pluralities, while getting herself over 15% in many congressional districts—the threshold for earning delegates. That would justify, to her online donor base, her continued presence in the race. The upward trajectory could be the beginning of a return to the top of the pack or, if no candidate is on track to secure a delegate majority, the establishment of enough niche support to be a player in a contested convention.

For Biden and Warren to steady their respective campaigns, both need to recognize who is in their way and strategize how to get past them. For Biden, the obstacles of Buttigieg, Klobuchar and Steyer (and, after South Carolina, Bloomberg) require a shift from an electability argument to a governability argument. For Warren, the obstacle of Bernie Sanders requires her own governability argument—arguing that she is better equipped than Sanders to deliver the ambitious agenda progressive populists want. Whether either lagging candidate is prepared to forcefully confront their most immediate rivals remains to be seen.

Source: https://www.realclearpolitics.com/