The Odds on a Contested Convention, and a Tie on Nov. 3

January 12, 2020#election2020 #DonaldTrump #electoralvotes #Democraticpresidentialprimary

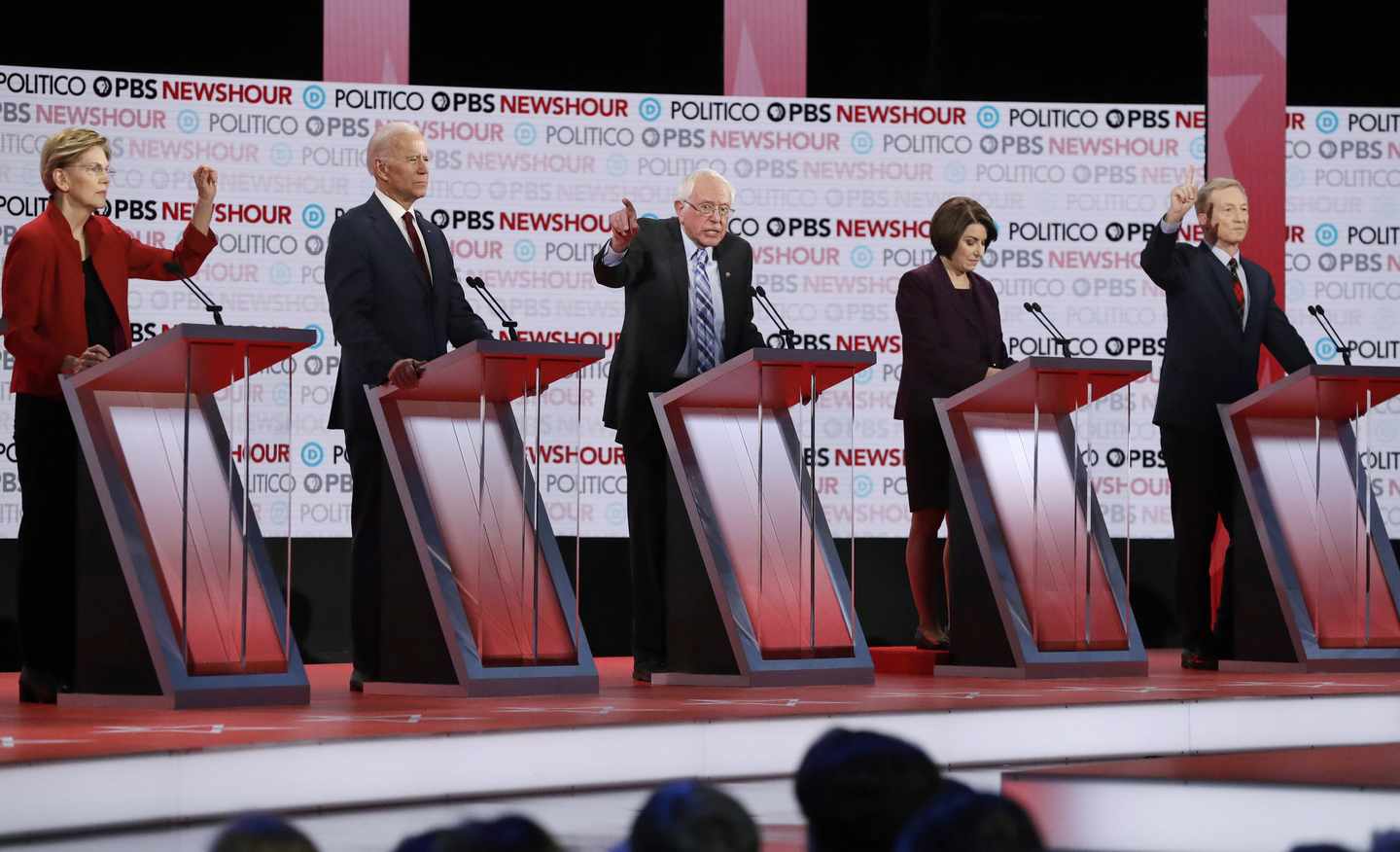

Although a single vote has yet to be cast in Iowa or New Hampshire, it’s tempting to ponder a pair of summer and autumnal spectacles that probably will go unmentioned in next Tuesday’s debate in Iowa, the seventh such gathering of President Trump’s challengers: a brokered Democratic National Convention, come July, and a “hung” presidential jury – 269 electoral votes for each candidate – come November.

The former, you should take seriously. The latter, not so much. Here’s why.

The last time either major party held a national convention that wasn’t a foregone conclusion was in 1976, when Ronald Reagan nearly wrested the Republican nomination from then-President Gerald Ford. Not since 1952 has either party gone past the first ballot in choosing its presidential nominee (unfortunately for Democrats that decade, voters weren’t “madly for Adlai”).

How could 2020 change this pattern? Look no further than the players in the game – and the game’s revised rules.

The last time Democrats had this much non-binary intrigue, this deep into the primary season, would be the 2004 nominating contest. But that competition ended swiftly after then-Massachusetts Sen. John Kerry swept Iowa and New Hampshire in January, then captured nine of 10 states in the March 2 “Super Tuesday” set of primaries and caucuses.

This year, Super Tuesday falls on March 3. Yes, it’s possible that one contender will wake up the following morning as the nominee-in-waiting, having plowed through February’s four primaries and caucuses and the 15 states at stake (including California and Texas) on the first Tuesday in March.

But consider this alternate universe: February’s four contests yield at least three different winners, then Super Tuesday likewise subdivides. By the end of March, with roughly two-thirds of the delegates off the table, there’s no candidate with a decided mathematical advantage, no aura of inevitability.

The race could drag into April and beyond (circle April 28 on your calendar, as it’s the day New York and Pennsylvania go to the polls), with at least five principal contenders – former Vice President Joe Biden; former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg; South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg; Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren and Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders – all splitting delegates, thanks to the party’s proportional allocation (unlike Republicans, Democrats don’t have winner-take-all primaries).

Should the outcome be in doubt once the candidates arrive in Milwaukee for the national convention? Superdelegates no longer can vote on the first ballot – not if the field lacks a contender possessing enough delegates to secure the nomination. What that means: the media dream of Democrats huddling behind closed doors – in whatever passes for a “smoke-filled room” in the America of 2020 – trying to find a consensus nominee.

As Jerry Seinfeld would say: good luck with all that.

Much less likely is the prospect of the Democratic nominee finishing in an Electoral College deadlock with President Trump.

At least two scenarios could produce a 269-all tie – one being that all states vote the same as in 2016, with Trump surrendering Michigan and Pennsylvania while the Democratic nominee flips Nebraska’s 2nd Congressional District, which barely went red in 2016 (Nebraska and Maine being the only two states that don’t allot electoral votes solely by statewide results).

The second scenario: The Democrat-to-be-determined flips Arizona, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, while Trump flips New Hampshire. Again, it’s a net loss of 37 electoral votes for Trump, down from the 306 he won back in 2016.

One problem with these scenarios: They assume volatility seldom seen in incumbent presidential elections.

In 2012, Barack Obama’s electoral vote count fell to 332, from the 365 he received in 2008 – the first such regression for a reelected incumbent since Franklin Roosevelt in 1944. Only two states flipped (both from blue to red): Indiana and North Carolina. In 2004, only three states flipped: New Hampshire turning blue; Iowa and New Mexico turning red.

The 1996 presidential election did see more volatility – Bill Clinton picked up Arizona and Florida; he lost Colorado, Georgia and Montana. However, there was a big difference in 1996: a less influential Ross Perot (he won only 8 million votes in his second presidential run versus 19 million four years previously).

A second problem with the electoral deadlock: the notion that, if President Trump’s house is on fire, it’s a controlled burn. Were Trump to lose Pennsylvania and Michigan, would Wisconsin buck the trend? If Trump lost Arizona, a state he won by 3.9 percentage points (making it the 10th closest state in 2016), what about the five other states that he carried by smaller margins – Michigan (0.3); Wisconsin (1.0); Pennsylvania (1.2); Florida (1.2%); North Carolina (3.8)?

Trump could “thread the needle” – i.e., shed a few states, like Obama, but not enough to fall below 269 electoral votes. But if Trump were to lose a traditionally Republican state that he carried by nearly four percentage points three years ago, does that forebode blanket doom in these six states that constitute 101 electoral votes (added to Hillary Clinton’s 232 electoral votes from 2016, the new sum is eerily close to Obama’s 332 electoral votes in 2012).

Of course, all of this is dependent on the Democrats choosing a nominee capable of simultaneously appealing to voters in the Sun Belt, the New South and a Rust Belt “Blue Wall” that Trump permeated in 2016 – while energizing the party’s base in ways that Hillary Clinton couldn’t, without further alienating the more cautious middle of the electorate.

Does such a Democratic unicorn exist? It’s worth pondering, in case you plan to watch Tuesday night’s debate. About the debating, which will be held at Drake University: Get used to it; it may be a while before this contest is settled.

Source: https://www.realclearpolitics.com/

Comment(s)