U.S. Catholics' Mood One Year Before the 2020 Election

December 9, 2019#election2020 #DonaldTrump #U.S.bishops #PopeFrancis #clergysexualabuse #Catholicvoters

A decisive majority of Catholic voters believe that the United States is becoming less hospitable to religious faith, according to an in-depth new survey of American Catholics. Asked whether they agree or disagree that people are becoming “less tolerant” of religion, 70% answered affirmatively. Only 25% disagreed. Moreover, by a margin of 2-to-1, registered Catholic voters (62%-31%) would like Christian values to play a more important role in society. This compares to the 54% of all registered voters who agree with this sentiment.

These are among the findings in the latest poll by RealClear Opinion Research. The in-depth survey of 2,055 registered voters (1,223 of whom were Catholic) was conducted Nov. 15-21. Done in partnership with Catholic-themed television network EWTN, the survey offers fresh insight into the mindset of a vast voting group long considered key to victory in national elections in this country.

“With few exceptions, for generations, tracking the preferences of the Catholic vote has proven to be a shortcut to predicting the winner of the popular vote -- and I expect 2020 to be no different,” said John Della Volpe, director of the RealClear survey. “Like the rest of America, the 22% of the electorate comprising the Catholic vote is nuanced and diverse. And like America, the diverse viewpoints based on generation, race, and ethnicity are significant and prove that no longer are Catholic voters a monolith.”

This was not always the case. In 1960, four out of five Catholic votes went to John F. Kennedy, which proved decisive in sending the first (and only) Roman Catholic to the White House. Over the ensuing decades, the Catholic vote has continued to trend Democratic -- although nothing like it was for JFK. Catholic voters remain crucial because there are so many of them: More than one-fifth of the electorate, according to the RealClear Opinion Research data. Yet they are so difficult to typecast, as Della Volpe and others note, because they don’t cast their ballots as a bloc.

“People who talk about ‘the Catholic vote’ as a monolith don’t know many Catholics,” said John Carr, director of the Initiative on Catholic Social Thought and Public Life at Georgetown University.

“This data poll confirms the differences in ethnicity, age, and ideology within the Catholic community that make it such a pastoral challenge for bishops and such an electoral opportunity for politicians,” Carr added. “Within the Catholic community, there are more swing voters than any other religious community and campaigns that ignore this reality will pay a political price.”

So let’s cut to the chase: How does Donald Trump stand with Catholics? The short answer is: not great. In mock matchups posed to registered Catholic voters (as with non-Catholics), the president trails Democrats Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and even the lesser-known Pete Buttigieg. Meanwhile, 55% of Catholics (and 54% of non-Catholics) in the survey support the impeachment and removal of Trump from office.

The more textured answer regarding Trump is this: It depends on which Catholics you ask. In 2016, Election Day exit polls showed him carrying the Catholic vote over Hillary Clinton 50% to 46%, a preliminary result encouraging to Republicans and disconcerting to Democrats. Particularly dismaying to Democratic Party leaders was a subsequent Pew Research Center analysis showing that a significant portion of Trump’s gains among Catholics had come from Hispanic voters. Later, however, a comprehensive analysis from the American National Election Studies concluded that Clinton actually carried the Catholic vote against Trump -- by a margin (48% to 45%) that mirrored her popular vote advantage nationwide. The definitive ANES analysis estimated that 74% of Hispanic Catholics voted for the Hillary Clinton-Tim Kaine ticket, with only 19% choosing Donald Trump and Mike Pence. The Republican ticket’s margin among white, non-Hispanic Catholics -- this is not unusual for GOP candidates -- was 56%-37%.

In 2020, however, Trump is running as an incumbent overseeing a booming economy, which -- as the president never tires of pointing out -- has led to record levels of employment among minority communities. So where does Trump stand today in the RealClear Opinion Research poll with Catholic Hispanics? The answer appears to be that he’s doing better than in 2016. But for the man who characterized Mexican immigrants as “rapists” in his 2015 presidential announcement speech, a chasm remains. While a clear majority (54%) of white Catholics approve of Trump’s job performance, less than one-third of Hispanic Catholics give him a thumbs up.

A partisan disparity runs through the Catholic community generally. Some 37% of non-Hispanic Caucasian Catholics say they are Democrats, while 42% identify as Republicans. By contrast, 60% of Latino Catholics are Democrats, while only 24% side with the GOP. In addition, while only 22% of white Catholics consider themselves liberal -- and 36% as conservative -- these numbers are virtually flipped for Hispanic Catholics (33% liberal, 26% conservative).

Another wide gap detailed in the RealClear poll -- and one likely to impact many elections beyond 2020 -- is generational.

Della Volpe’s survey reveals that 56% of registered Catholic voters under age 35 are Democrats, while only 23% are Republican (with 20% identifying as independent).

In comparison, Baby Boomers and other Catholics over age 55 break out this way: 45% Republican; 36% Democrat; 18% independent.

Among Catholics 55 and older, 45% identify as conservative, with only 15% self-describing as liberal. Among Catholics between the ages of 18 and 34, however, these numbers are upside down: 39% are liberal, nearly twice as many who identify as conservative.

Donald Trump is not immune from this generational undertow: While 55% of Catholics over 55 years old approve of the job he is doing as president, only 34% of younger voters give him high marks.

This gap goes beyond politics and suggests weighty implications for American Catholicism itself.

In the question about whether Christian values should play a more important role in American life, the 62% of Catholics who answered affirmatively were not evenly distributed by age. Although Della Volpe found no significant differences based on race and ethnicity on this question, the generational fault lines were stark: Older Catholics overwhelmingly embrace that idea, with 80% answering affirmative and only 13% saying no. Younger Catholics, in contrast, are evenly split on this question.

Younger Catholics were also significantly less likely than older Catholics to credit Christianity for having a “positive influence on American culture.” Likewise, less than half (48%) of younger Catholics report that they accept all (16%) or most (32%) of the church’s teachings. More than two-thirds (69%) of Catholics 55 years or older say they do accept all or most church doctrine.

These findings have momentous potential implications for the future of the Catholic Church and the Republican Party. Put most simply: Those least committed to the church’s teachings and to Christianity itself are its younger adherents. Those most committed to the faith – like those most committed to the GOP – are older. In other words, a critical mass of the most loyal Republicans and most devout Catholics are gradually aging out of the population. This suggests that a generation from now, the GOP and the Catholic Church will look different.

Change is part of life, however, even in an ancient institution that prides itself on being built on “the rock” of the Apostle Peter. No less an authority on Catholic teaching than Pope Francis has said that he believes “the Lord wants a change in the Church.” How that change will manifest itself inside Catholicism -- and in secular U.S. elections -- is an unfolding story. In the meantime, not even Francis himself can escape the magnetic pull of partisan U.S. politics.

A Pew Research Center poll done earlier this year found a striking correlation between American Catholics’ political affiliation and their views of the pope. “There was a time when Catholics in both parties were largely united in their admiration for Pope Francis,” wrote Pew analysts Michael Lipka and Gregory A. Smith. “But in recent months, even these views have become more polarized along party lines, with Catholic Democrats and Democratic leaners viewing Francis more favorably than Catholic Republicans and GOP leaners.”

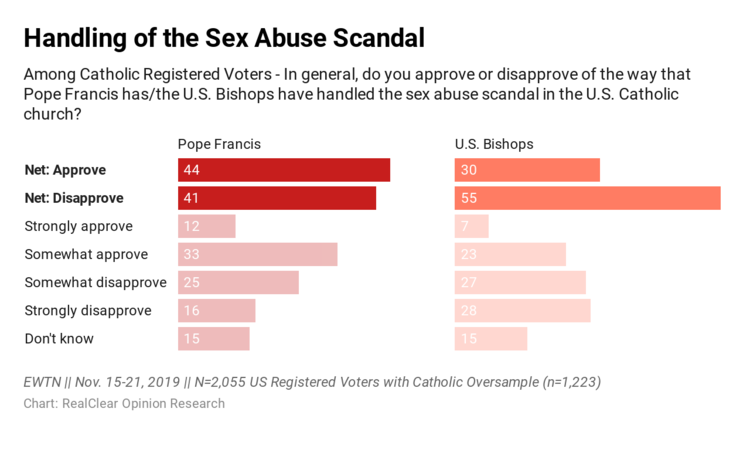

Nonetheless, the RealClear Public Opinion Research poll found than when it comes to the sex abuse scandal that has roiled Catholicism worldwide, American Catholics view Francis more favorably than they do their own bishops. A plurality of Catholics, 44%, approve of the pope’s handling of the crisis, with 41% saying they disapprove. These aren’t great numbers, but the pope ranks much higher than the U.S. bishops: Only 30% of Catholics approve of their handling of the matter, compared to 55% who disapprove.

The widespread desire for reform is not limited to reining in sex abuse. Majorities of Catholic voters across the board favor allowing priests to marry (64% of all Catholic voters, 58% of the most devout) and for women to be ordained as deacons (69% of all Catholic voters, 64% of the most devout). Della Volpe defines the most devout Catholics as those (58%) who say they accept “all” or “most” of the church’s teachings. Another way to think of this cohort is the people who are most active in their faith. When House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said last week that she prays for Donald Trump, she was associating herself with this kind of Catholic. These devout Catholics, according to RealClear data:

- Pray at least once a week (93%).

- Believe in the “real presence of Christ” in the Eucharist (66%)

- Attend Mass at least once a week (55%)

- Go to confession at least once a year (52%)

- Pray the rosary at least once a month (51%)

The Nancy Pelosi example is instructive. A product of a Catholic upbringing and education, the House speaker is also a lifelong Democrat. She attended John F. Kennedy’s inauguration as an unmarried Catholic-college student then named Nancy D’Alesandro and met JFK in the White House at age 20. In the ensuing decades, a majority of observant Catholics of her generation have gravitated to the Republican Party. As a rule, they have parted company with the Democrats on public policy issues, especially abortion, a subject in which the Democratic Party and the Catholic Church have deep doctrinal differences. In this sense, conservative Catholics are similar -- at least in their voting patterns -- to evangelical Protestants.

But that cohort of Protestants is not as monolithic as they seem. Even as legacy pastors like Franklin Graham and Jerry Falwell Jr. garner headlines and evangelical intellectuals flagellate their community over its support for Trump, new generational attitudes are emerging among evangelicals as well. Fifteen years ago, University of Akron professor John C. Green concluded from his research that as many as one-third of evangelicals were political moderates and potential swing voters who are more liberal than the generic GOP candidate on issues ranging from poverty to the environment. They may not be familiar with Catholic social thought -- or even know that phrase -- but they are certainly aware, for instance, of Jesus’ admonitions about caring for the poor, just as they are keenly aware of Trump’s moral shortcomings.

Nonetheless, the Democrats’ absolutism on abortion, the party’s rapid drift leftward on economic issues, and its acquiescence to the most esoteric demands of identity politics have kept evangelicals in the Republican camp. This paradigm isn’t likely to change, especially as the Democratic Party radicalizes itself from the inside. As for Catholics, well, that is still an unfolding story.

“If the patterns of recent decades hold, the weekly-Mass Catholics will skew heavily Republican in 2020, as the Christmas-and-Easter Catholics will skew heavily Democratic,” says conservative Catholic intellectual George Weigel.

“Whether what I’ve come to think of as ‘Trump Exhaustion Syndrome’ will cut into that Republican vote among active Catholics (as distinguished from nominal Catholics), I can't say,” Weigel added. “But if the Democrats keep pushing each other farther and farther to the cultural left, there may be a strengthening of the Catholic vote for Republicans, however implausible a vehicle for the cause of cultural renewal the chap at the head of the ticket is.”

That, too, may ultimately change -- and not because Trump leaves the scene, but because he, like all of his fellow Baby Boomers, will eventually cede the national stage to Millennials and members of Gen Z. Already, they are making their views felt. On the hotly debated issue of “Medicare for All,” for example, Catholics are more likely than non-Catholics to “strongly” support such a system -- even one that eliminates private insurance. These numbers are driven by overwhelming support for the plan among Latino and young Catholics.

“Catholic voters are the largest Christian denomination in battleground states like New Hampshire, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania,” noted Della Volpe. “Since 1952, they have voted for the winner in 13 of 17 presidential elections. Whether or not younger Catholics turn out to vote at close to the same levels of their parents and grandparents could well decide the 2020 election in these states, and with it the future direction of our country.”

Carl M. Cannon is the Washington bureau chief for RealClearPolitics. Reach him on Twitter @CarlCannon.

Source: https://www.realclearpolitics.com/

Comment(s)